Unlocking Desire a Play & Screenplay by Barbara Neri

Artist/Director Statement

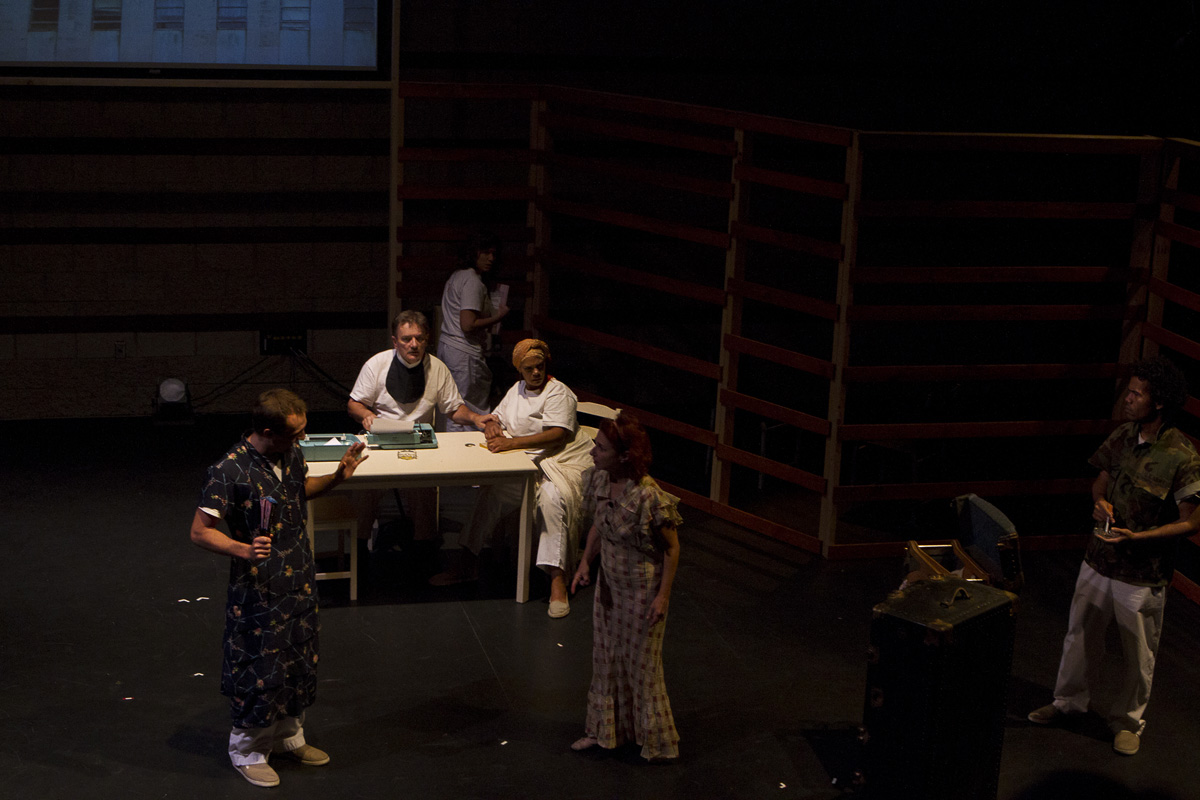

I know all the characters in this script. I met many of them while visiting my brother Jim while he was in a nursing rehab facility in the late stages of an illness. 'Ozzie' and 'Jim's' relationship is modeled after Brenda and Ron, a couple who sat with Jim at meals. Brenda had suffered too many strokes and was almost blind. Ron survived a suicide attempt but the gunshot wound to his head caused seizures. To spite their tragic circumstances, they found love and shared a room in the facility. My brother Jim died there and his wife Rose died a few months later. 'Raoul' is a fusion of many friends, in particular David who died in the 1980s of a then mysterious illness. 'Hank' is named after my father, a WWII Paratrooper. 'Rose' evokes Tennessee Williams beloved sister as well as my sister-in-law. 'Blanche' embodies the despair of so many people right now, it would be difficult to list them all. 'Violante' has many of the wise and strange qualities of my late mother-in-law. But as with the other characters, her name evokes another. She is named for Violante do Ceo, an old forgotten poet. But she also evokes all the old strong Spanish women in Lorca’s Trilogy. Williams loved Lorca’s work; and I believe the brief but important role of the 'Mexican Woman' in A Streetcar Named Desire is an homage to Lorca, as my 'Violante' is.

As a writer I am interested in how we tell our love stories: Who is & isn’t entitled to love’s redemption? I am (among other things) asking the audience if the abandoned characters in Unlocking Desire are entitled to Love. This discourse on Love has gone on for millennia, and it is played out largely in love poetry: Petrarch, Dante, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, among others. Unrequited love, or failure, is usually the topic. But in the case of Barrett Browning, love triumphs and spirit and flesh are not in conflict but rather become one. The poetic discourse intersects with, and is fleshed out in, the theater and film. It certainly intersected thusly for Williams, for he was a poet (first) and he knew what he was doing when he alluded to Barrett Browning in Scene 3 of A Streetcar Named Desire.

What was he doing? His allusion has been overlooked although he made a point of directing our attention to the final lyric of Barrett Browning’s love Sonnet (and by association her and Robert Browning’s love story) twice in A Streetcar Named Desire's pivotal Scene 3:

“And if God choose, I shall but love thee better – after – death!”

I am an artist first and my scholarly enquiries spring from my artistic process. This research is the fertile ground from which Unlocking Desire emerged. Establishing Williams’ engagement with the poetic discourse on Love is important (for him and for us). The Browning’s (heterosexual) romance became part of the cultural consciousness via the theater in the very popular Rudolph Besier play The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1930). Williams reported it was the first play he ever saw: in St Louis during the depression he saw Katharine Cornell's 1934 production. This production is part of theater history involving Cornell and her director/producer husband Guthrie McClintic. Though it is generally acknowledged that their marriage was lavender, their professional partnership was both fruitful and legendary. Williams admired them both, and was at first writing the role of Blanche DuBois for Cornell. How The Barretts of Wimpole Street, Barrett Browning's life and her love sonnets intersects with A Streetcar Named Desire is a complex dynamic that was personal, poetic and aesthetic for Williams. And his use of the darker, final lyric of Barrett Browning's 'Sonnet XLIII' is very telling. This is how artists engage in the discourse on love. My research linking Williams to this ancient and ongoing discourse has now been published in The Tennessee Williams Annual Review number 17, 2018.

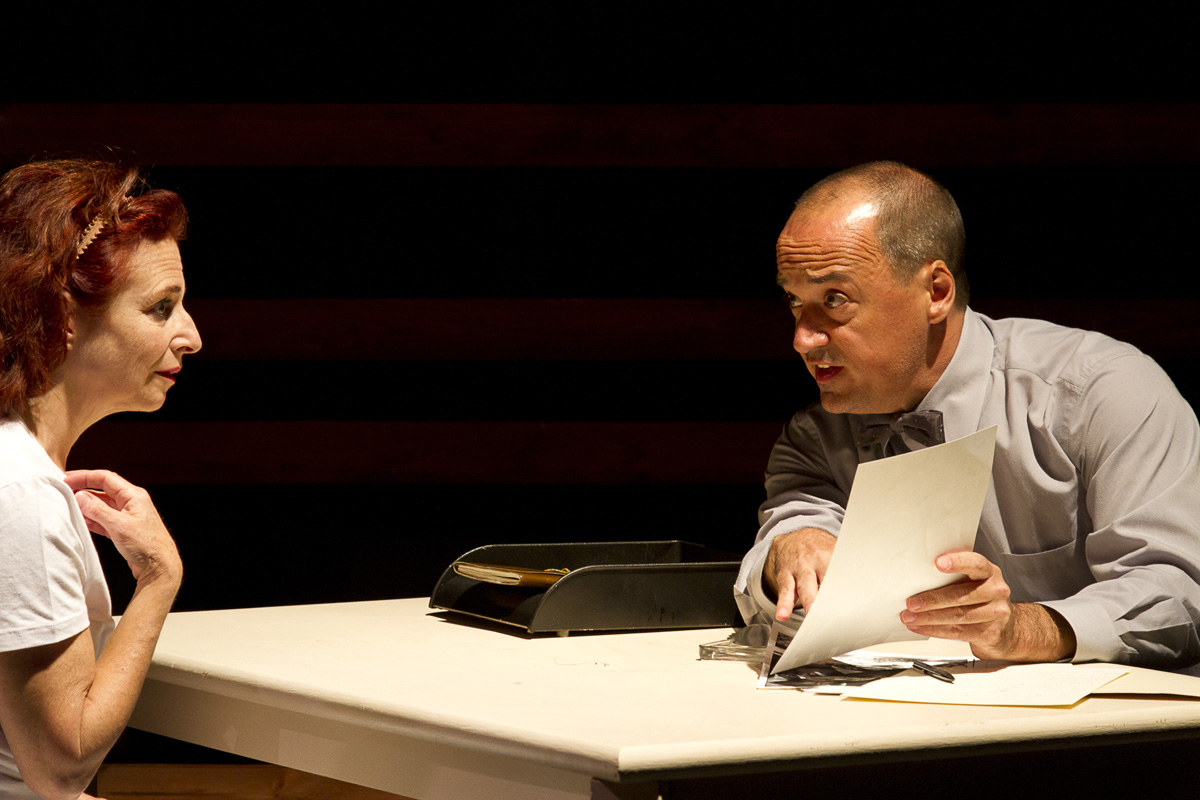

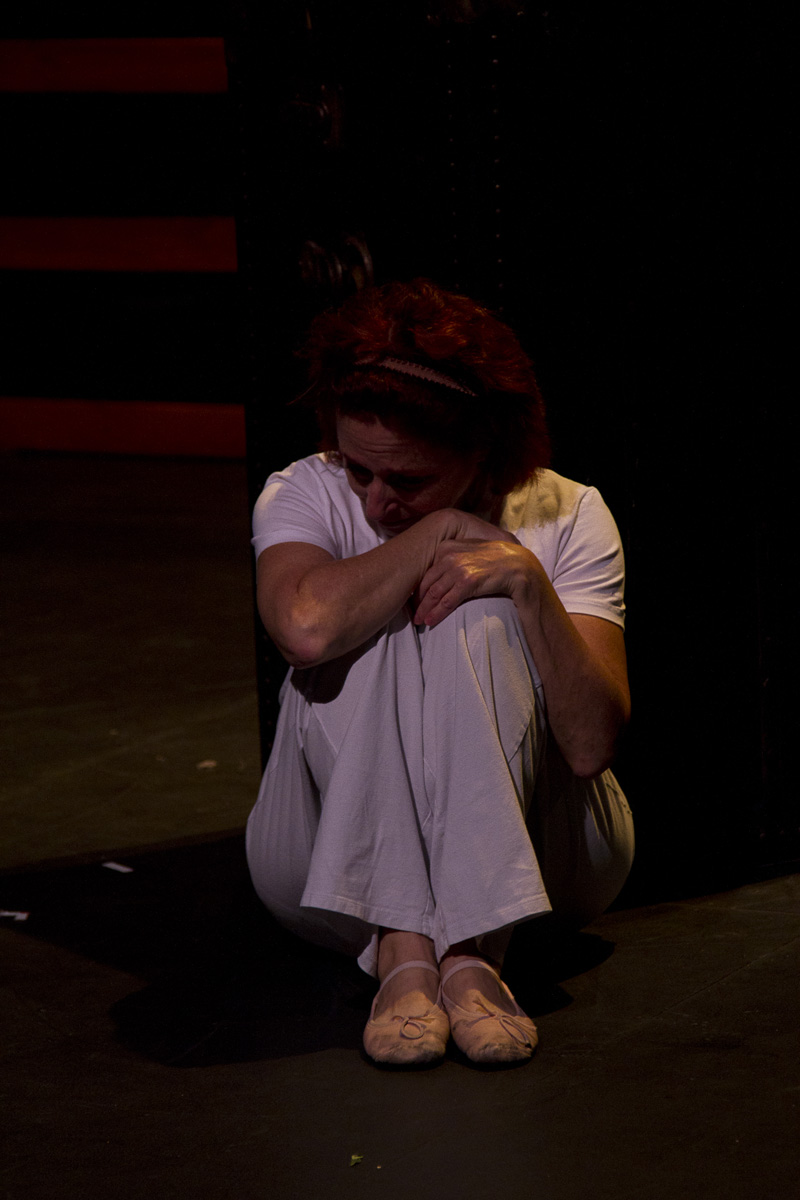

Among the love stories evoked in Unlocking Desire is that of 'Blanche DuBois' and 'Allan Grey.' Allan was Blanche’s first love and they ran off together to marry at age 16. I've always wondered why this was allowed to happen. Blanche's family was affluent and she was educated; so why did her family allow her to run off and marry at 16? And why did Allan's family look the other way and allow this? When I literally did the math I arrived at a very interesting answer that is relevant to us today, given not only the 2008 recession going on when I did research for Unlocking Desire in New Orleans, but also the ongoing widening gap between wealthy and poor. That said, there is another romance in Unlocking Desire that attempts to emerge, and this ray of hope is initiated by 'Hank'. But Blanche is blind to the love around her, as if she is cursed.

It is ‘Ozzie’ that tells Blanche that she has to 'make her peace with that boy' (Allan) once and for all. Ozzie is named after and evokes Williams’ beautiful childhood nursemaid. Ozzie was African American and a storyteller. Williams mentioned her often, but her impact on him as a writer has never been factored. Thus it became important to give her a presence and voice in Unlocking Desire. Ozzie and Blanche have a pivotal dialogue in a dream, during which Blanche both speaks for the character ‘Blanche DuBois’ but also as her creator Tennessee Williams. This layering of the biographical and fictional is embedded into the text throughout Unlocking Desire. The layering of fact and fiction is always an important dynamic of Art.

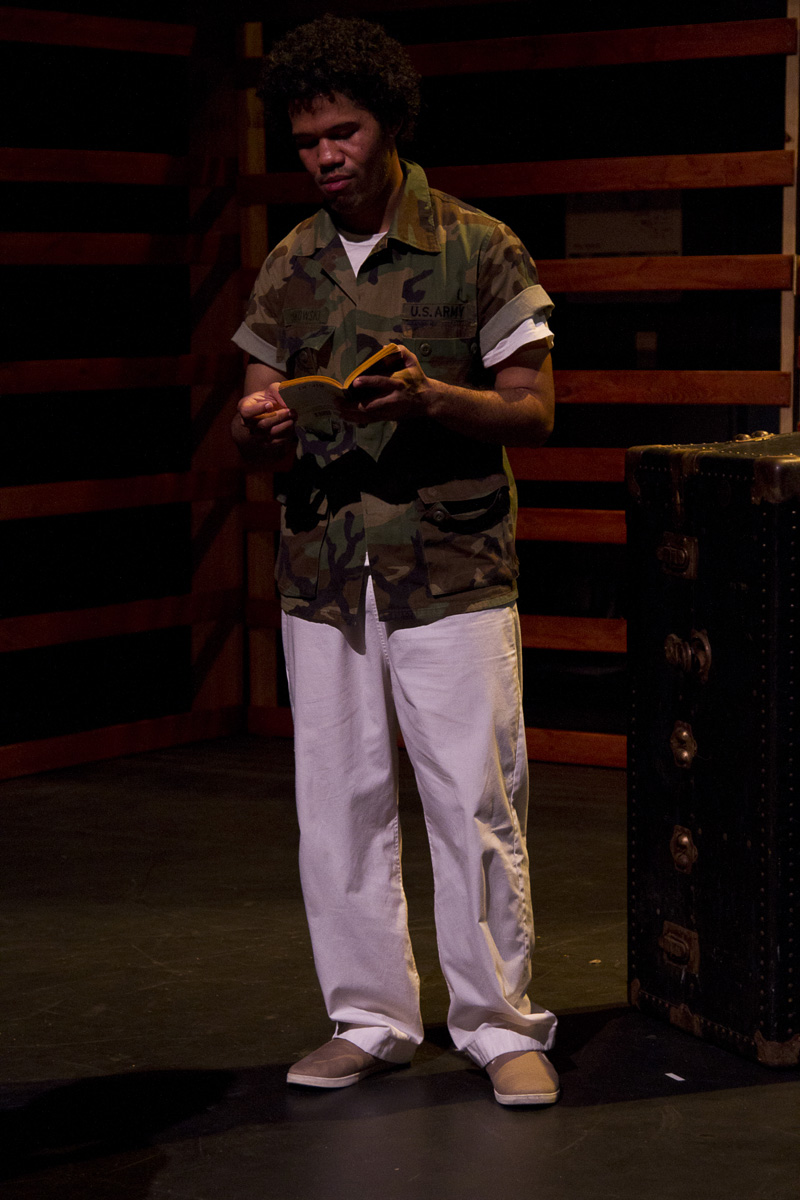

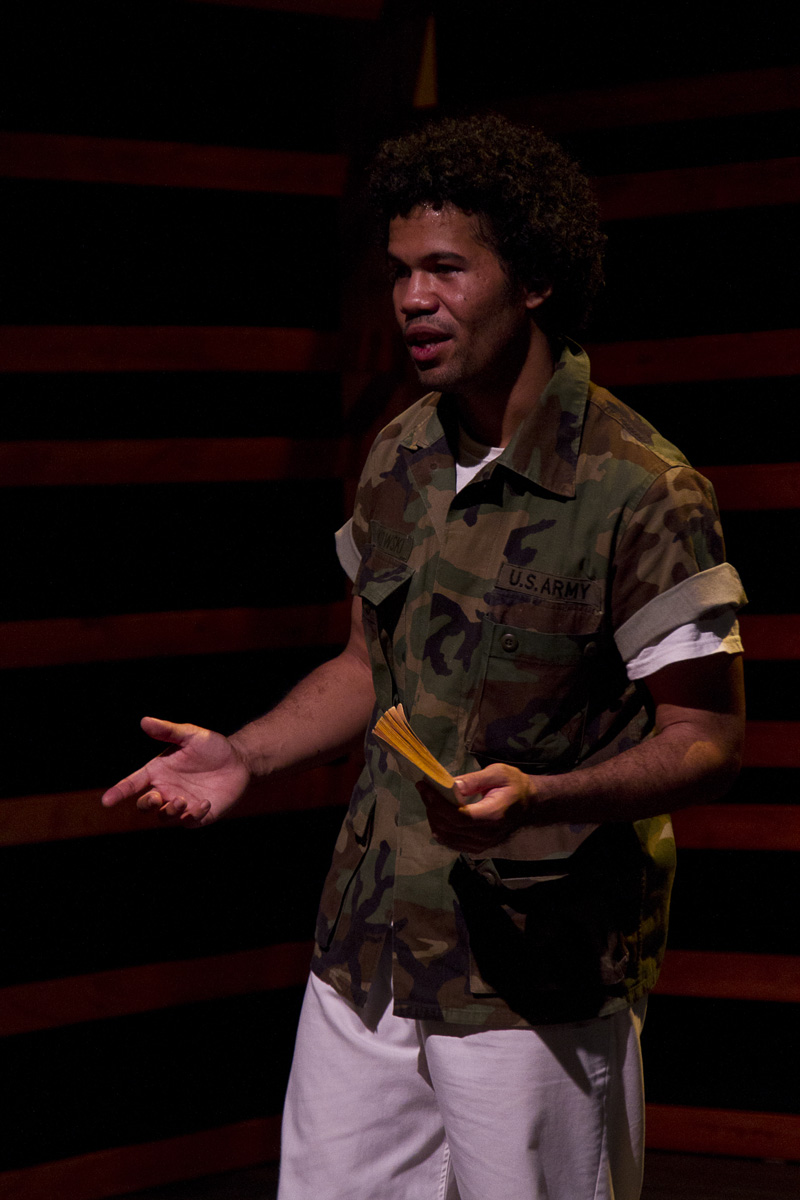

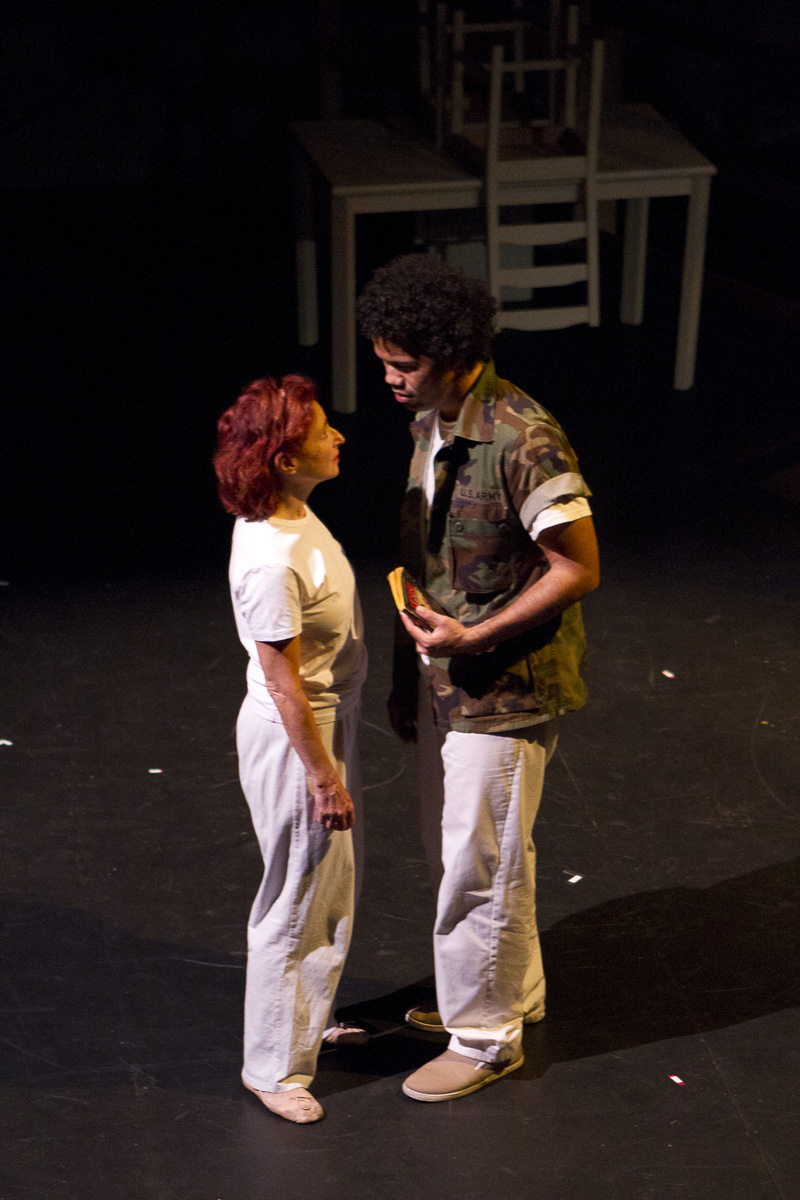

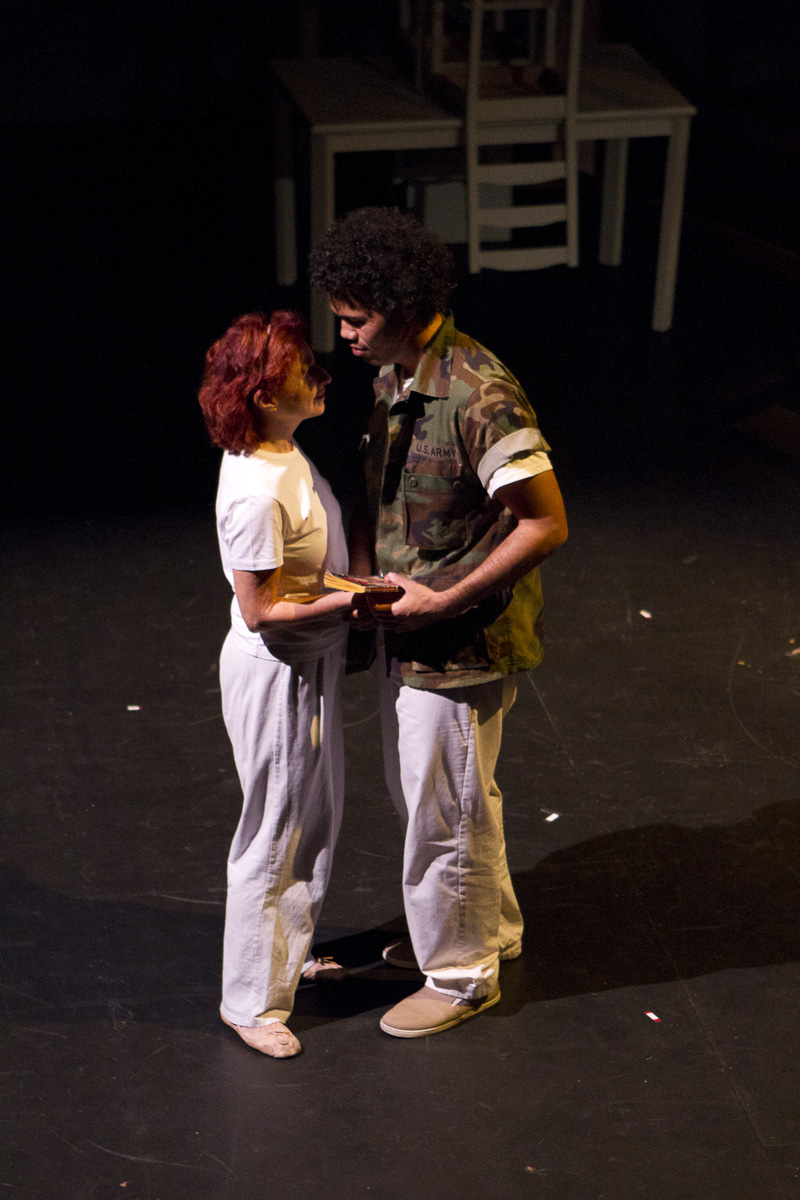

'Allan Grey' is not a character in Unlocking Desire, rather his story is present through another character named ‘Raoul.’ And 'Raoul' also evokes a person from Williams' life, the dancer Kip Kiernan. Of course Allan’s story is still with us today and thus it is realistic and relevant that Raoul would be in the institution, placed there by his wife, after he attempted suicide when his wife discovered his homosexuality and confronted him. Blanche is unable to move on until she can talk to Allan again and via Raoul she is mysteriously able to do so. Blanche serves a similar purpose for Raoul, in that he must look at Blanche and see the impact his suicide would have had on his wife, had he succeeded.

Historically, certain writers and their characters become iconic and inform our consciousness. Exploring their back-stories becomes necessary and relevant. Can we write a new story into existence, i.e. change consciousness, without bringing them with us? Often when I talk to people about Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire it is apparent that if they know the play, it is via Elia Kazan's 1951 film version. Thus, because the film was censored, they do not know the play. It is my desire to not only infuse my writing with such censored & critical ideas, but also unlock the secrets still in play today that underpin the beliefs that continue to hold us hostage.

Research for Unlocking Desire was also conducted in the Williams Research Center at The Historic New Orleans Collection and on the streets of the city of New Orleans during August 2008. Among other things, I took part in a Vodou ceremony. I had conversations with people on the streets about Williams' work, and a few of their thoughts are integrated into Unlocking Desire. The former Convergence Art Center hosted a discussion group during which I viewed the Kazan film of A Streetcar Named Desire with artist members. Interestingly, the young women in attendance had little sympathy for Blanche DuBois. They thought she was just crazy and hysterical until I told them how the Allan Grey story was censored. After learning how Allan had betrayed Blanche, and his tragic end, they could sympathize with her and feel the tragedy and the ongoing relevance of Williams’ play in our still homophobic society. Thus the importance of exploring this ongoing tragedy in Unlocking Desire became pertinent.

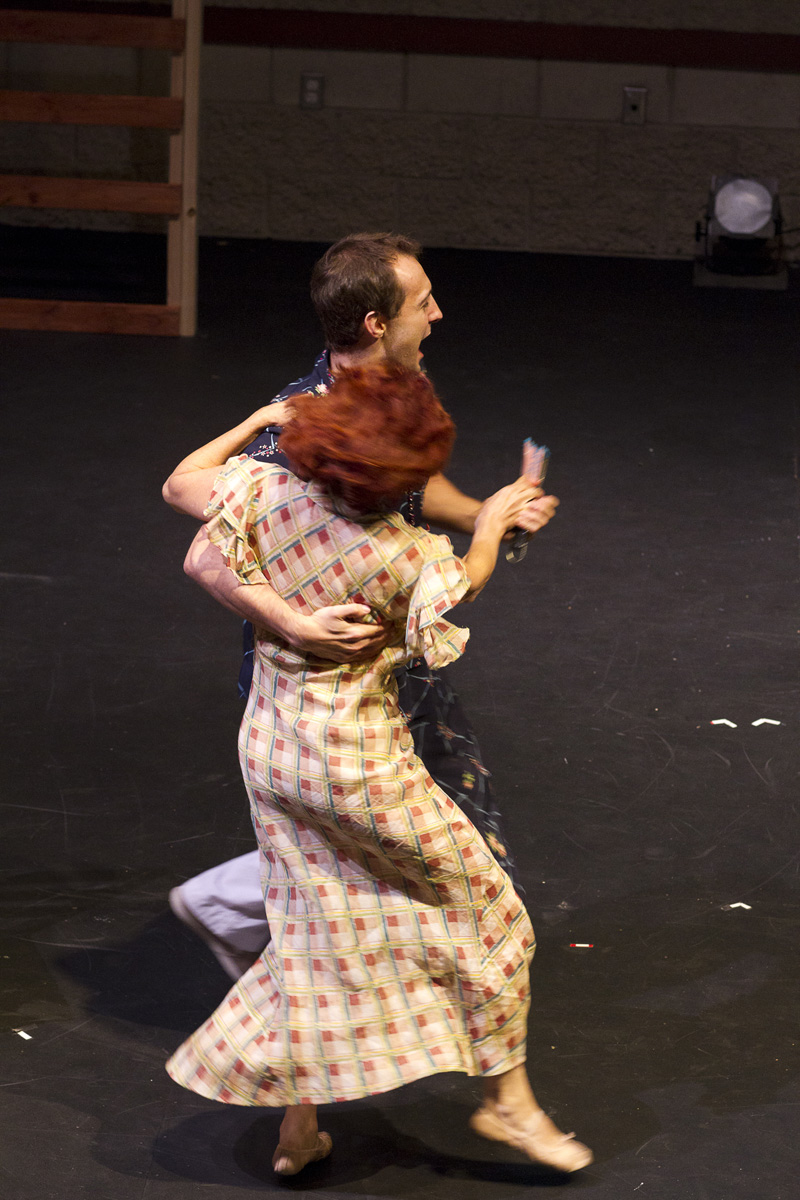

Also, while I was in the Williams Research Center at The Historic New Orleans Collection , I looked at Vivienne Leigh’s collection of photos from the Kazan film set. Many of them were obviously of a film set: with boom mics and other film equipment exposed as the actors performed. It suddenly became glaringly apparent to me that, though Blanche DuBois is powerfully iconic, she is not real. I wanted the audience to experience this revelation and see Blanche as a real woman of today, traumatized and mysteriously lost in the world of Williams’ play. Thus the inmates she meets in the institution remind her of shadow characters in the play (and people from Williams' life); and the inmates, unbeknownst to themselves, ‘play’ their parts...but all is not as it seems!

Finally, plays and screenplays emerge from an accumulation of experiences that reach a critical mass. When I think back to the moment that this play may have hatched in my consciousness, I recall the 2003 shotgun murder of Nikki Nicholas, a young transgender person, in a farmhouse not far from where I live:

http://atranspt.blogspot.com/2007/02/four-years-later-nikki-murder-still.html

I was sickened by this and wanted to reach out somehow. I called and met with the late Jeff Montgomery when he was director of the Triangle Foundation (now Equality Michigan). We talked about Love and what I was trying to accomplish with my work as a writer and scholar. We talked about the idea that change has to happen on a deep level, and this must involve our consciousness. Art, Films, Plays, the literary cannon and how works are read, explained and taught in schools inform this consciousness. This is in essence the ground water that feeds the public tap. Writers and artists of all stripes are beckoned to engage in this and correct, revise history. This is challenging but necessary work. And it is part of a long process I have been involved in and that Unlocking Desire is part of.

September 8, 2011 / Updated June 2018

Barbara Neri